9

Cimarron, First of the Fast Tankers

Two weeks after the construction contracts for the twelve national defense tankers subsidized by the maritime commission were formally signed, Adm. William Leahy wrote the commission to advise that the Navy Department wanted to acquire the first of these tankers immediately upon its completion.1 Leahy intended to include the cost of four large auxiliaries authorized, but not yet funded, in his budget estimates for the coming year (FY 1939), and it is clear that he intended to acquire one of the subsidized oilers as soon as possible.2 Four days after Leahy's letter, the House of Representatives, finally awakening to the growing unrest in Europe and now concerned with the need to strengthen America's defenses, passed its version of the annual naval bill for FY 1939.3 Exceeding all previous peacetime appropriations for the navy, this legislation would provide Leahy with the funds needed to procure the auxiliaries authorized but not funded in the previous year, including the oiler so desperately wanted by Leahy.

Construction of the twelve national defense tankers ordered by the maritime commission began on 25 April 1938.4 On that date the keel for the first of these vessels, Cimarron, was laid at the Chester yards of the Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company. The following day, President Roosevelt signed the Naval Appropriation Act for FY 1939, allocating $140 million for new ship construction.5 By then, both houses of Congress were nearing agreement on a billion dollar naval expansion bill, which would become known as the Second Vinson Act.

Introduced in early January by Carl Vinson, chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee, the proposed bill would increase the size of the navy by 20 percent. On the very day Vinson first presented the measure, Roosevelt again interceded on behalf of the navy delivering a strong, special message to Congress stressing the need to maintain

--98--

military strength in both oceans and in regions far beyond American shores.6 When signed into law on 17 May, the final version of Vinson's bill (Public Law 528) authorized appropriations for 46 more fighting ships, 26 auxiliaries, and 950 airplanes.7 Funding to commence work on the first 9 auxiliaries scheduled, including 4 oilers, was quickly appropriated by Congress on 25 June 1938.8 With the passage of this act, the navy had authorization and funding to construct or acquire a total of 5 modern fleet oilers.

With the ships in the Kanawha class now approaching or exceeding twenty years of age, the navy did not have any oilers capable of keeping up with the modern, fast warships that were rapidly joining the fleet in growing numbers.9 To expedite the addition of this much-needed type, the Navy Department decided to acquire, by way of the U.S. Maritime Commission, three of the high-speed tankers then being built for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. Because of the backlog in the navy's yard and the heavy workload in the Bureau of Construction and Repair, the department estimated that it could shave at least a full year off of normal delivery time if it took this route. Although Standard Oil readily agreed to the transfer, its legality was uncertain, leading to a series of discussions between the maritime commission, the judge advocate general of the navy, and the comptroller general of the United States.10 After a lengthy exchange of legal opinions, the president was asked to act on the matter at his discretion "under the terms of the statutes involved."11

The navy's position was expressed by Adm. James O. Richardson, commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet, and acting secretary of the navy, who was charged with placing the facts before President Roosevelt. His letter to the president on 12 August 1938 reads in part as follows:

My dear Mr. President:

With a view to obtaining three high speed tankers for the use of the Navy in the shortest possible time, the Navy Department, with the maritime Commission, has investigated the possibility of acquiring three of the tankers already under construction for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. . . .

The acquisition of these three tankers through utilizing the services of the U.S. Maritime Commission, as authorized by the Act of June 30, 1932 (31 U.S.C., 686) [Economy Act], will make the vessels available to the Navy at least a year earlier than if the required contract plans and specifications were prepared to permit competitive bidding and direct contracts entered into by the Navy. In addition, it is estimated that there will be a saving in Government funds if the proposed acquisition is approved of $1,500,000 or more per vessel. . . .

--99--

This matter is of such importance to the National Defense that it is submitted to you for your approval.

The president endorsed Richardson's letter as noted below:

Arrangements for the acquisition of the three vessels took several more months to execute as new contracts had to be drawn up transferring the tankers to the maritime commission upon completion and reimbursing Standard Oil for the cost of construction and any incidental expenses incurred in delivering the ships to the navy. Although the first ship was not scheduled for completion until April 1939, its delivery was moved up at the request of the navy. A formal agreement verifying the new arrangement was apparently signed on 27 October 1938, though a public announcement was not made until November when Standard Oil issued a statement to the press stating it had sold the Cimarron and the Neosho, two of the twelve high-speed tankers then under construction, to the navy at the contract price of $3,130,000.12

Cimarron, first of the National Defense Features (NDF) tankers to be completed, slid down the ways at the Sun yard on the morning of 7 January 1939. At the time of her launching, the Cimarron, with an overall length of 553 feet and a beam of 75 feet, was the fastest tanker built in the United States and one of the largest in the world. The lines plan chosen for her hull form was designed specifically to enhance the high-speed characteristics desired by the navy and was radically different from that used on any previous tanker. The design was based on the latest advances in naval architecture, had been refined by extensive testing in the navy's model basin, and included a bulbous bow--the first ever to be used on a tanker. This feature was intended to improve the ship's performance by reducing the wave-forming resistance generated as the ship moved through the water. Cimarron also had a distinctive clipper bow, which with its raked stem was designed to improve sea keeping.

Acceptance trials, which had to be conducted before Standard Oil assumed ownership, were held off the coast near Rockland, Maine, during the first week of February 1939. In a series of test runs conducted to determine her best performance, Cimarron maintained an average speed while fully loaded of 19.28 knots developing an impressive 16,900 s.h.p.13 After successful completion of the trials, the ship was delivered to the Philadelphia Navy Yard where she was formally accepted by a representative of Standard Oil, legally sold to the U.S.

--100--

Cimarron,first ship completed for the U.S.

Maritime Commission, as she appeared during her trials in February

1939. (Author's collection)

Maritime Commission, and immediately transferred to the navy's account on 6 February.

While at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, the Cimarron underwent preliminary conversion to a navy oiler. This involved minor changes to the ship's gear needed to bring her up to navy standards. In the main, this involved the addition of communication equipment, boats, and other gear not carried by commercial vessels but needed for naval service. No armament was added during her brief stay at the navy yard, and it does not appear as if any major changes or additions were made. Full conversion to a fleet oiler would not take place until her first major overhaul eighteen months hence.

When officially commissioned on 20 March 1939, the Cimarron became the first new oiler to join the fleet since the ill-fated Tippecanoe was mothballed in 1922. Assigned hull number AO-22, the huge tanker was immediately sent to Houston to load a cargo of fuel oil destined for the naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. She made a total of thirteen trips to Hawaii carrying oil from the West Coast before returning to

--101--

Philadelphia for overhaul and modifications (to be described in chapter 10), which would turn her from a dowdy merchantman to a bristling goddess of war.14

Neosho (AO-23) and Platte (AO-24)

Though the Navy Department would have liked to acquire the second and third of the National Defense Tankers laid down for Standard Oil, these had already been promised to the Keystone Shipping Company and were unavailable. Still, arrangements were made with Standard

Neosho, as delivered to the U.S. Navy in

August 1939. View looking forward from after deck house shows complex

piping typically found on oilers. (National Archives)

--102--

TABLE 10

Principal Dimensions of Cimarron (T3-S2-A1) as Delivered

|

| Length, overall |

553 |

feet |

| Length, between perpendiculars |

525 |

feet |

| Breadth, molded |

75 |

feet |

| Deadweight (approx.) on 30-foot draft |

16,734 |

tons |

| Deadweight (approx.) on 31-foot, 71/8-inch summer draft |

18,200 |

tons |

| Cargo capacity |

147,150 |

bbls |

| Trial speed |

18 |

knots |

|

Oil for the navy to acquire the next in line, MC Hull No. 6, laid down at the Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company yard in Kearney, New Jersey, on 22 June 1938. Launched on 29 April 1939, she was christened Neosho (after a river in Kansas) by Mrs. Emory S. Land who was given the honor of sponsoring this, the fifth ship to be completed in the program and the second to be acquired directly by the navy.15 [Neosho was preceded by Cimarron, Seakay launched 4 March, Markay also launched 4 March, and Standard Oil's Esso New Orleans launched 1 April.)16 After completion of her trials, Neosho was delivered to the navy and equipped for service, though like the Cimarron, she would not be fully converted into a fleet oiler for some time. The Neosho was commissioned on 8 August 1939 and immediately pressed into service transporting fuel oil needed by the fleet.

The Platte was the last of the navy oilers acquired in 1939. Though she was the sixth National Defense Tanker to slide down the ways

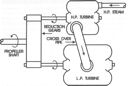

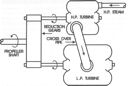

Fig. 6. Turbine arrangement of the Cimarron class

--103--

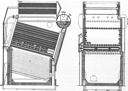

Fig. 7. Cutaway drawing of Babcock & Wilcox boiler (U.S. Maritime Commission)

when launched on 8 July 1938, she was the first of those completed by Bethlehem Steel's yard at Sparrows Point, Maryland. The Platte was delivered to the Norfolk Navy Yard on 1 December 1939 and commissioned the same day as hull number AO-24. She was sent to the Philadelphia Navy Yard after commissioning to be converted for naval use, but unlike her recently commissioned sisters, Platte underwent extensive modification (see chapter 10) before entering service.17The complexity of the contractual arrangements concluded between the U.S. Maritime Commission, Standard Oil of New Jersey, the four builders, Keystone Shipping, and the Navy Department has created a good deal of confusion concerning the origins of this uniquely important series of vessels and the circumstances surrounding their transfer to the U.S. Navy. The fact that three NDF tankers were delivered and placed into service with two different shipping companies and the U.S. Navy in the same year (1939) has only added to the uncertainty surrounding the early history of these vessels. Even more confusing is the manner in which those taken into the navy were armed and converted to fleet oilers. It is hoped that the preceding discussion as well as the succeeding chapters will put this issue to rest.

--104--

View of typical boiler room of a Cimarron-class oiler.

Though designed for 13,500 s.h.p., the four B&W boilers

generated enough 450-pound steam to furnish the 16,000 s.h.p. needed

for the 19+ knot trial speed attained by these vessels. (National Archives)

View of typical boiler room of a Cimarron-class oiler.

Though designed for 13,500 s.h.p., the four B&W boilers

generated enough 450-pound steam to furnish the 16,000 s.h.p. needed

for the 19+ knot trial speed attained by these vessels. (National Archives)

Design Characteristics of the T3-S2-A1 Tanker

In addition to being the lead ship in her class and the first of the National Defense Tankers, the Cimarron carried the distinction of being the first of five thousand plus ships delivered to the U.S. Maritime Commission.18 She was designated as a T3-S2-A1 type by the maritime commission in accordance with the classification system established for identifying the various designs adopted by the commission for its ships. Under this system, the T stood for a tanker, the 3 indicated a length greater than 500 feet, S2 referred to the propulsion system--which in this case was steam turbine with twin screws--and A1 meant that it was the first design of this type.

The Cimarron and her twelve sisters were originally designed and constructed as twin-screw bulk oil carriers of the three-island type having a single continuous freeboard deck, with raised poop, bridge,

--105--

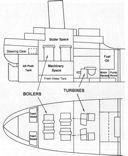

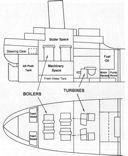

Fig. 8. General machinery and boiler arrangement for Cimarron-class oilers

and forecastle sections. Below decks, the main hold of these ships was subdivided by twin longitudinal bulkheads interspersed with a series of transverse bulkheads, which divided the interior of the ship into twenty-four main cargo tanks. Two more cargo tanks were squeezed into spaces just forward of the forecastle where the hull began to taper inward. Each ship was also fitted with two steel masts mounting a 5-ton boom and had two Samson posts with 1-ton handling booms. Special attention had been paid to providing fireproof construction, and a carbon dioxide system for extinguishing fires was installed in the cargo tanks. Principal dimensions of the T3-S2-A1 as delivered are shown in table 10.

--106--

Machinery and Equipment

The T3-S2-A1 type was a twin-screw vessel powered by dual marine steam turbines of the most advanced design. Each set contained a high-pressure and a low-pressure turbine mounted in separate casings. An astern turbine for reverse thrust was also provided within the low-pressure casing. Both turbines individually developed 6,750 s.h.p. at the normal propeller speed of 96 r.p.m. and were separately connected to one of the shafts by a set of double-reduction gears (fig. 6).19

Steam for the main turbines, auxiliaries, and cargo pumps was supplied by four Babcock & Wilcox sectional header watertube boilers designed for a working steam pressure at the superheater outlet of 450 pounds per square inch and a total temperature of 750 degrees Fahrenheit. The boilers were fitted with Todd oil burners and Hagen combustion control. Other principal equipment included two main condensers and one auxiliary condenser, both manufactured by Westinghouse; and two General Electric 400-kilowatt 230-volt 3-phase alternating current geared turbo-generator sets (fig. 7).20

Pumps for transferring cargo were located in two oil-cargo pump rooms, one aft and one amidships. The after pump room was located just forward of the machinery spaces and was equipped with three Ingersoll-Rand centrifugal main cargo pumps actuated by motors mounted in a separate compartment. The after pump room also contained a stripping pump of the vertical steam-turbine reciprocating type manufactured by Worthington Pump. The amidships pump room was located just aft of the island bridge structure and was equipped with two Worthington, steam-actuated, vertical reciprocating main cargo oil pumps and a Worthington stripping pump similar to that in the after pump room (fig. 8).

--107--

Contents

Previous Chapter (8) **

Next Chapter (10)