13

Naval Expansion and the Acquisition of Additional Oilers

On 6 January 1940, Adm. James O. Richardson relieved Adm. Claude C. Bloch as commander in chief, United States Fleet. He was somewhat disturbed to find that a considerable detachment of the fleet, consisting of cruisers and destroyers, had already been sent to Hawaii in anticipation of the maneuvers scheduled for the spring. The rest of the fleet departed its West Coast bases on 2 April and was scheduled to return after completion of Fleet Problem XXI, which was to be conducted in the vicinity of the Hawaiian Islands. At the end of the exercises, however, the chief of naval operations, Adm. Harold E. Stark, ordered Admiral Richardson to station the fleet at Pearl Harbor where it would be in a better position to deter possible Japanese aggression in the East Indies. Richardson complained bitterly to Admiral Stark about the lack of support services at Pearl Harbor and argued unsuccessfully against stationing the fleet there on a permanent basis.1

Keeping the fleet at Pearl Harbor adequately supplied with fuel was a major problem due to the long distances involved and the navy's lack of modern oilers. All fuel oil had to be transported 2,000 miles from the West Coast to Pearl Harbor, which required a round trip of at least two weeks when the time to load and discharge cargo was included. Only the new high-speed tankers of the Cimarron class were suitable for this purpose, as the other oilers in the fleet were in such bad shape that they could not be used on a continuous basis.2 Although the Cimarron and the Neosho had already been pressed into service shuttling oil between the West Coast and Hawaii, their combined capacity was not sufficient to both replenish the fuel consumed during normal operations and build up a reserve. While the addition of the Platte increased the number of Cimarron-class oilers in commission to three, it did not relieve the shortage of tankers on the West Coast

--135--

since the Cimarron, now in need of a routine overhaul after thirteen voyages, was sent to the Philadelphia Navy Yard for the six-month conversion described previously (see chapter 10).

During the late spring and early summer of 1940, events in Europe and the increasing threat of U.S. involvement in an overseas war galvanized Congress into passing a series of acts that had a profound effect on the U.S. Navy. Prior to this time, the navy's construction efforts had focused on building various types of combatants. The status of naval auxiliaries had not changed appreciably since the early 1920s. Most were old and "almost all [were] still lacking in speed."3 Although a program to build modern auxiliaries had been initiated, Congress was still reluctant to appropriate funds for any non-fighting warship. This situation changed dramatically between June and July as a direct result of the fall of France and the growing threat in the Pacific. In the relatively short space of five weeks, Congress passed two major appropriation bills and three regulatory acts that immediately doubled the allowable size of the fleet and changed the manner in which all new vessels were procured.

The first of these measures, the "Third Vinson Bill" passed on 14 June 1940, authorized an 11 percent increase in the combatant tonnage of the fleet. This bill was followed on 20 June by the "Reorganization Bill," which created the Bureau of Ships (BuShips), consolidating the functions of the Bureau of Engineering and the Bureau of Construction and Repair under one roof. Four days later, on 24 June, Congress passed another act abolishing the Construction Corps, eliminating the staff position of constructor, and transferring all former members of the corps into the regular navy as "engineering duty only" officers (EDOs). The fourth bill passed during this period was the "Speed Up Act" of 28 July. Enacted to expedite the procurement of ships, the act authorized the secretary of the navy "to negotiate contracts for the acquisition, construction, repair or alteration of complete naval vessels," eliminating the need to secure competitive bids as had been the policy in the past.

The fifth and final bill was the most significant of all. Passed on 19 July 1940, it called for a whopping 70 percent increase in the authorized tonnage of the navy and became known as the "Two Ocean Navy Act." In addition to increasing the authorized size of the fleet, the Two Ocean Navy Act also authorized large expenditures for patrol craft, shipbuilding facilities, ordnance plants, armor plants, and 100,000 tons of additional auxiliary vessels!4

The navy wasted no time in taking advantage of these new provisions and immediately began to take the steps necessary to acquire additional oilers through the maritime commission. By the end of August, the chief of naval operations had directed the newly established Bureau of Ships to prepare plans for converting two of the maritime

--136--

commission's Cimarron-class tankers that were closest to delivery. On 7 September, the CNO directed that the first of these, the Esso Albany, which was scheduled for completion on or about 15 September 1940, receive "a preliminary conversion of about ten weeks duration at the Navy Yard, Philadelphia, to accomplish substantially the same work that was done on the Platte (AO-24) during her preliminary conversion."5 The Esso Columbia, then under construction at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company yard was the next Cimarron-class tanker scheduled for completion. Since the Esso Columbia was not expected to be completed before February 1941, BuShips was instructed to arrange to have the present contract modified so that the ship can have incorporated in it during the building period such changes as are now contemplated for the Cimarron-class upon final conversion.6

The Esso Albany was acquired as scheduled and immediately commissioned as Sabine (AO-25). Although the Esso Columbia was officially acquired by the navy in November 1940, the ship did not join the fleet until April 1941 when she was commissioned as the Salamonie (AO-26). Salamonie appears to have been converted as planned since she was the only other ship of her class, besides the Cimarron and the Platte, modified to carry the full complement of four 5-inch, 38-caliber guns originally called for.

On the day that Sabine was acquired, 25 September 1940, the secretary of the navy wrote to the maritime commission stating the navy's desire to acquire two more of the Cimarron-class tankers with delivery expected in September of the following year.7 The maritime commission agreed to undertake design and construction of these vessels for the navy; a conference was held at the Bureau of Ships on 3 October 1940 to discuss additional features that the navy wanted added to the ships while they were still under construction.8 No sooner had these arrangements been made than the secretary of the navy issued a directive requesting the immediate transfer of the Esso Trenton, Esso Richmond, and Keystone Seakay to the Department of the Navy.9 All were sister ships of the Cimarron and were thus subject to requisition by the navy under the provisions of the Merchant Marine Act of 1936.

This action appears to have been triggered by Japan's unexpected signing of the Tripartite Pact and its implications for the deployment of additional elements of the U.S. Fleet. In October 1940, Admiral Richardson traveled to Washington, D.C., to lobby for the fleet's return to the West Coast. He lunched with President Roosevelt on 8 October, reiterating his objection to maintaining the fleet in Hawaii--a position that was to cost him his post as commander in chief, U.S. Fleet. Two

--137--

The SS Esso Albany under way.

Completed for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, she was

acquired by the navy after passage of the Two Ocean Navy Act of

1940. (National Archives)

The SS Esso Albany under way.

Completed for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, she was

acquired by the navy after passage of the Two Ocean Navy Act of

1940. (National Archives)

--138--

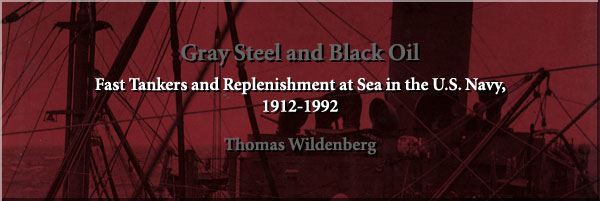

Kaskaskia (AO-27) leaves Mare Island Navy Yard 15

December 1941. Her arrangement is typical of the T3 tankers acquired

after 1940, though the forward mounts appear to contain one

5-inch, 50-caliber and one 3-inch, 25-caliber gun--probably the only

weapons then available in the rush to arm every ship during the first

month of the war. (National Archives)

Kaskaskia (AO-27) leaves Mare Island Navy Yard 15

December 1941. Her arrangement is typical of the T3 tankers acquired

after 1940, though the forward mounts appear to contain one

5-inch, 50-caliber and one 3-inch, 25-caliber gun--probably the only

weapons then available in the rush to arm every ship during the first

month of the war. (National Archives)

days later, on 10 October, Richardson attended a conference in the office of Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to discuss plans for employing the U.S. Fleet, including a new proposal by Roosevelt calling for the establishment of a line of patrol ships along two lines in the Southwest Pacific. Also in attendance were the chief of naval operations Adm. Harold E. Stark, the assistant chief of naval operations Rear Adm. Royal E. Ingersol, Capt. Charles M. Cook, Jr., of the War Plans Division, and Cdr. Vincent R. Murphy, Richardson's war plans officer. What transpired just prior to this meeting is not clear, though it seems likely that the decision to acquire still more oilers (i.e., the Esso Trenton, Esso Richmond, and Seakay) was made in response to Richardson's continued concerns regarding his logistic problem with the fleet.10

Within a few days of the secretary of the navy's directive to acquire the three additional tankers, the CNO instructed the Bureau of Ships to prepare these vessels for the fleet so that they would be available for service on the Pacific coast no later than 1 December 1940.11 All three were immediately acquired and delivered to various navy yards where their fitting out was assigned as a first priority over new construction.12 The three vessels were rapidly converted and entered naval

--139--

service before the end of the year as the Kaskaskia (AO-27), Sangamon (AO-28), and Santee (AO-29). By the end of 1940, only four of the twelve national defense tankers originally ordered: the Esso Annapolis, Esso New Orleans, Esso Raleigh, and Keystone Markay were still in commercial service. They too would be taken over by the following June becoming the Chemung (AO-30), Chenango (AO-31), Guadalupe (AO-32), and Suwanee (AO-33).

--140--

Contents

Previous Chapter (12) **

Next Chapter (14)