18

Combat Logistic Support Emerges as an Integral

Component of Operational Planning

By the end of the Leyte operation, fueling at sea had become so ensconced in the navy's thinking that its impact on future planning warranted comment from none other than Adm. William "Bull" Halsey. As was the practice at the end of every operation, each unit's commander was required to submit an "after action" report to his superior, which was then passed up the line. In his report, Capt. J. T. Acuff, the man in command of Task Group 30.8, the logistic group at sea, recommended that because of the vulnerability of the slow-moving oilers, one escort vessel be provided for each tanker, and one for each carrier loaded with aircraft replacements.1 Halsey agreed with Acuff's assessment and went on to point out important lessons learned, another ritual that the navy used in the Second World War to disseminate combat experience. Halsey's comments, presented here, provide a general summary of the replenishment doctrine then in use by the Third Fleet.

(a) There has been too great a tendency to discount the need for adequate escorts for oiler and CVE groups. We have been extremely lucky; our oiler groups for STALEMATE were pure submarine bait. A minimum of one escort per oiler and two per CVE should be provided. This will become important as we move closer to Empire waters. Also, for extensive long-range operations, one fleet tug and one salvage ship should be assigned with each group of three oilers which are kept at sea in advanced positions.

(b) Operational control of replenishment and service elements through the establishment of such agencies as 30.8 (At-Sea Logistic Group) and 30.9 have worked out well in practice and it is recommended for consideration (in future operations?).

(c) Proficiency in fueling at sea by all units should continue to be emphasized as vital military necessity. The doctrine that all ships make approach on oilers is sound and should be standardized. In estimating oiler requirements for an operation as much emphasis should be placed on number of oiler sides available for

--190--

simultaneous fueling as on total quantity of oil required. A little extravagance in number of oilers will pay big dividends when time is an essential factor. Two large ships may be fueled simultaneously from one oiler under favorable conditions with some sacrifice of pumping rate. In order to complete the fueling of a large force expeditiously, destroyers must be fueled by heavy ships waiting their turn to fuel from tankers. . . . It is feasible with favorable wind and sea conditions to fuel two battleships simultaneously from one tanker. Due to the possibility of crushing the tanker, this practice should not be resorted to excepting in emergency when the possible loss of the tanker is secondary consideration. . . .

(d) Third Fleet experience indicates that the staff of a Task Fleet Commander must include a line officer widely versed in oiler matters and concerned with oiler operations, and also an officer of the supply corps familiar with the operations, capabilities, and limitations of that Service Force.2

Halsey was not alone in taking an interest in this increasingly important logistic operation. In November 1944, COMINCH (Headquarters of the commander in chief U.S. Fleet) issued a comprehensive set of instructions for fueling at sea intended to "serve as a guide for those to whom the exercise is totally unfamiliar." Like the after action reports, the instructions were intended to make available in easily accessible form, the knowledge gained from the experience of many ships who had performed this task.3

When this document bearing a "Restricted" classification was published, the navy considered the broadside method as the standard means for fueling vessels at sea. Although experienced crews had found that they could do without the tow line, the procedure spelled out in the "Instructions" dictated that one of the vessels involved (usually the larger) was to tow the other at a comparatively close distance--40 to 80 feet alongside. This operation was not considered a deadweight towing task, but rather "an exercise in position keeping aided by a towline."4 Though the towline was intended to act as an aid in station keeping, oiler crews had learned that they could make do without it after the Gilbert Island operation (see page 181). Instead of a towline, one vessel would maintain position on the other adjusting her engine speed and using a "seaman's eye" to correct for small changes in position drift due to wind or sea so the two vessels would maintain steady position on each other.

Fuel oil was normally dispensed from four oiling stations located on the well deck, two on each side, port and starboard. After the first few months of wartime operations, it was deemed necessary to mount the cargo winches (used for manipulating the saddles that supported the heavy hoses) onto one or more spar decks constructed above the well deck. This much-needed addition permitted the fueling detail to

--191--

Although the

broadside method was the primary means for fueling at sea, diesel oil

was normally dispensed from the fueling station aft using the astern method. Mattole (AO-17) uses this method on 17

August 1944 to refuel the diesel-powered escort destroyer Pride (DE-323). (National Archives)

Although the

broadside method was the primary means for fueling at sea, diesel oil

was normally dispensed from the fueling station aft using the astern method. Mattole (AO-17) uses this method on 17

August 1944 to refuel the diesel-powered escort destroyer Pride (DE-323). (National Archives)

work above the turbulent waters that swirled along the well deck as the heavily laden tankers plowed through the deep Pacific swells (see photograph on page 181). The structural changes needed to provide this new deck were retrofitted to each oiler as it came in for routine overhaul and were added to the plans drawn up for the wartime construction programs. The largest of these spar decks was located just forward of the after deck house and covered most of the well deck. As the war progressed, it was used as a general cargo deck for storing and/or issuing all sorts of general cargo, extra boats, and the innumerable lines, hoses, and fittings that comprised the fueling gear. Why this function was not included in the original conversions is puzzling since virtually every oiler in the prewar navy had been modified in this manner. It may be that this knowledge was lost during the lean years of the 1930s when development work came to a standstill in the interest of economy.

As mentioned, the fuel hoses, even when empty, were heavy and difficult to handle.5 A 210-foot long, 6-inch diameter hose was normally used to transfer the heavy fuel oil to all ships larger than a destroyer. It was assembled from 50-foot lengths of collapsible hose and 20-foot lengths of heavy duty hose arranged in alternating sections.

--19--

The entire assembly was supported by two saddles suspended from the oiler's booms attached to the first two 20-foot sections of hose; the last section was taken aboard the receiving ship. If a destroyer was to be fueled, then the last 20-foot length of 6-inch heavy-duty hose was replaced by a 30-foot section of 4-inch, unless destroyers only were scheduled for fueling in which case seven lengths of 4-inch hose (each 30 feet long) were used. The smaller hose was considerably lighter when filled with fuel oil and was, therefore, much easier to handle and less wearing on the handling lines.6

Several different types of handling lines were needed to pass the hose to the receiving ship, keep it clear of the water, and retrieve it as soon as pumping was stopped. These included:

1. Hose line--Attached to the hose clamp on the outer length of hose and passed to the ship receiving the hose to haul in the end of the hose rig and return the hose end when fueling was finished.

2. Easing out line--Attached to the hose clamp on the outer length of hose and retained by the oiler, for easing out and retrieving the hose.

3. Outer bight line--Attached to the outboard hose saddle and passed to the ship receiving the hose (not used in fueling destroyers and smaller vessels).

4. Inner bight line--Attached to the outboard hose saddle and retained by the oiler. (Although most "type" plans showed this as a 5-inch manila line, most oilers were using a 3/4-inch wire rope by 1944. This was attached to a wire drum on the fueling-at-sea winch and run through appropriate wire blocks.)

5. Saddle falls--Attached to the inboard hose saddle and retained by the oiler.

Proper tending of the bight lines was the most critical part of the entire operation. As the ships moved in or out, or rolled toward each other, winch operators on both ships continually adjusted the height of the saddles in order to prevent the hose from trailing in the water or stretching so far as to cause the hose to break. Using fast winches, they tried to keep the angle between the bight line and the easing out line and the vertical equal: making an upright V. These men had to be constantly alert and needed to react quickly to changes in the relative position of the two ships, otherwise the hose might part, halting the transfer of fuel.

Except for battleships, carriers, and large cruisers, the ship to be fueled would normally maintain position on the oiler that would keep a steady course and speed. Under average weather and sea conditions, two ships could be simultaneously fueled at once, although the older tankers were limited to fueling one large ship at time. Except for dispensing diesel fuel, the astern method was considered an emergency measure only to be used when weather, sea, or other conditions prevented the use of the broadside technique.

--193--

The cluttered well deck of a Kennebec-class oiler as her deck crew stands

by during fueling operations conducted in smooth seas. Note the fuel

line has been assembled from various lengths of 6-inch-diameter rubber

hose. Compare the saddle details--which remained essentially unchanged

from the 1920s--with those in the photograph on page 33. (National Archives)

The cluttered well deck of a Kennebec-class oiler as her deck crew stands

by during fueling operations conducted in smooth seas. Note the fuel

line has been assembled from various lengths of 6-inch-diameter rubber

hose. Compare the saddle details--which remained essentially unchanged

from the 1920s--with those in the photograph on page 33. (National Archives)

Since fueling at sea was necessitated by fleet or ship movements far from base, it was expected that this activity would normally occur in a combat area and that the ships involved would be exposed to potential hostile action by enemy forces. It was important, therefore, that the operation of fueling at sea be conducted in the shortest possible time, to reduce the period during which the fueling vessels were vulnerable

--194--

to attack. It was to be assumed that attack was imminent, even during a drill, and no effort was to be spared to reduce the time needed for refueling. As the following paragraph illustrates, crews had to be ready to disconnect immediately, should they encounter the enemy.

The operation [fueling] must be conducted in a manner that will permit immediate cessation of operations for offensive action against a chance belligerent. All gear and rigging must be constantly tended and the handling crew must be trained to disconnect everything and return all gear instantly when so ordered. In so far as practicable, it is important that the burden of all possible rigging and handling thereof be assumed by the oiler, to enable combatant ships to go into condition I with the least possible delay.7

By the end of the war, oilers were routinely transferring

stores and munitions while conducting fueling at sea. Extra belly

tanks for aircraft and containers of ammunition were often stowed on

the open spar deck. The tall ventilator/kingpost combination and the

round cargo tank hatches identify this as a Chiwawa-class oiler.

(National Archives)

By the end of the war, oilers were routinely transferring

stores and munitions while conducting fueling at sea. Extra belly

tanks for aircraft and containers of ammunition were often stowed on

the open spar deck. The tall ventilator/kingpost combination and the

round cargo tank hatches identify this as a Chiwawa-class oiler.

(National Archives)

--195--

During the later stages of the war, several oilers were usually assigned the task of fueling an entire group of combatants at one time. To speed the operation and minimize the total time required for fueling a group of ships, a fueling schedule was made up in advance with each oiler assigned to fuel one type of ship if possible. This avoided having to change the fueling rig between ships, thereby shortening the overall fueling time for the group. This was not always feasible, however, and although type plans for fueling each class of ship had been drawn up by the various navy yards, the solution was a standard hose rig that permitted an oiler to fuel several ships of different types in rapid succession.

By the fall of 1944, the task of the oilers assigned to the logistic support group at sea had been expanded to include the replenishment of ammunition and stores. In addition to fuel--oil, aviation gasoline, and diesel fuel--oilers were also expected to provide a stock of lubricating oils (approximately two hundred drums, fifty cases) as well as limited quantities of (1) gases--including aviator's breathing oxygen, carbon dioxide, Freon, acetylene; (2) provisions, general stores, clothing, and ship's stores; and (3) ammunition and depth charges.

Although the broadside method was successfully used throughout the war, the need for both ships to steam within close proximity to one another made fueling in rough weather extremely hazardous. Collisions occurred even in relatively calm seas. Once in a while one ship would sidewipe the other as happened while the Kaskaskia was fueling the Yorktown (CV-10). To overcome this problem, a new fueling rig was suggested by one of the Cimarron's officers, which would permit ships to maintain a greater degree of separation, as much as 180 feet, while fuel was transferred.8

Various configurations of the new arrangement were extensively tested by the Kaskaskia during a two-week period in December 1944.9 With the Hart (DD-594) serving as the receiving ship, the two vessels perfected the new rig while refueling some fifty times under all conditions of sea and weather. Handling of the heavy fuel hose was made easier by using a 7/8-inch span wire rigged between the two ships. Wheeled trolleys supporting the hose cradles ran along the span, thereby relieving some of the weight on the saddle whips. The new rig, called the "Elwood method" after its originator, enabled ships engaged in fueling to remain separated by 60 to 180 feet. Later designated as the "wire-span method," it allowed greater speed through the water while fueling, provided for easier station keeping, and made maneuvering easier. This was a great operational improvement since fueling operations no longer had to be conducted into the wind, as had formerly been the case during most operations, and fueling became less dangerous in rough weather.

--196--

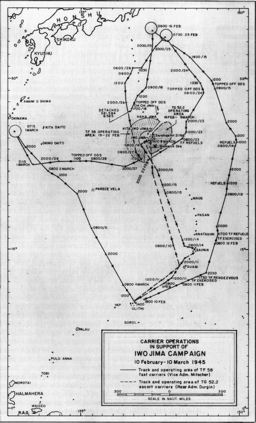

Service Squadron 6 and the Invasion of Iwo Jima

As the Fifth Fleet10 began to plan for the invasion of Iwo Jima in the fall of 1944, there was active discussion between staff members as to improved methods that could be used to provide additional logistic support in forward areas. Vice Adm. William L. Calhoun, commander Service Force, Pacific Fleet, recommended that a "combat logistic support squadron" be formed to permit maintaining the fleet at sea for unlimited periods of time.11 The mission of this squadron would be to "furnish direct logistic support to the Fleet, in and near the Combat Zone, in order to maintain the mobility and striking power of the Fleet."12 The proposed squadron would appear as a numbered task group in the task organization of the combat fleet (either Fifth Fleet or Third Fleet), and would be composed of ships capable of maintaining fleet speeds and supplying fuel, food, ammunition, airplanes, clothing, general stores, pilots, and personnel. Except for its flagship, the new squadron would be composed of supply ships and oilers temporarily assigned to it from other units. In command would be a rear admiral. Because of its proximity to the combat fleet, the new squadron would have to operate within the combat zone. This necessitated the addition of destroyers and escort carriers for screening and air cover.

On 25 November 1944, Rear Adm. Donald B. Beary was ordered to duty as commander Service Squadron 6. The new squadron, which bore no relation to the earlier squadron of mine layers, was established on 5 December 1944 to provide mobile logistic support to the fleet during the upcoming invasion. The old light cruiser Detroit (CL-8) was assigned as flagship and a temporary headquarters set up at Pearl Harbor in order to assemble a staff and establish logistic plans for the intended operation. The Detroit, with a staff of fifteen officers in addition to Rear Admiral Beary, sailed from Pearl Harbor in January 1945. Units of the squadron were formed at Eniwetok and Ulithi early in February for participation in the attack on Iwo Jima, with Squadron 6 designated as the Logistic Support Group Fifth Fleet, Task Group 50.8.

The formation of a logistic support group capable of providing all of the fleet's logistic needs at sea was a natural extension of the development of fueling at sea. Freed from the need to return to port for fuel, the fleet's ability to remain at sea was limited solely by the need to replenish ammunition, food, stores, and aircraft. Incorporating ammunition ships and stores ships into the at-sea logistic group (airplane transports--the CVEs--were already included) solved this problem. Establishing underway replenishment groups allowed the Fifth Fleet the freedom to roam the sea without having to return to port--a degree of seaborne mobility not seen since the days of sail.

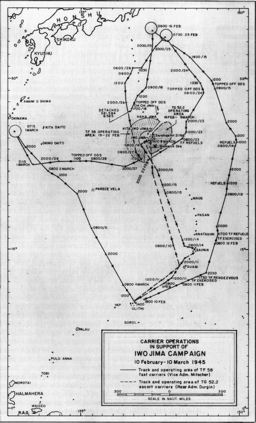

The significance of this strategic capability was aptly demonstrated during the campaign to capture Iwo Jima. Between 10 February and

--197--

Destroyer and carrier simultaneously taking fuel from a T3

tanker on 19 December 1945. This photograph was taken from the Altahama one day after the typhoon that struck

the Third Fleet capsizing several destroyers. Note the damage to the

catwalk and the plane tipped behind the stack. (National Archives)

Destroyer and carrier simultaneously taking fuel from a T3

tanker on 19 December 1945. This photograph was taken from the Altahama one day after the typhoon that struck

the Third Fleet capsizing several destroyers. Note the damage to the

catwalk and the plane tipped behind the stack. (National Archives)

10 March 1945, Task Force 58, containing the fast-carrier elements of the Fifth Fleet, was continuously at sea conducting wide-ranging combat operations (see map 1) in support of the invasion. During this thirty-day period, Task Force 58 steamed in excess of 7,500 nautical miles (excluding the mileage off Iwo Jima) and was refueled no less than three times using the procedures previously developed for refueling task groups at sea.

Between 8 February and 5 March 1945, Squadron 6 deployed twenty-seven oilers to provide fueling-at-sea support for all the elements of the Fifth Fleet. Within this time, the squadron delivered 2,787,000 barrels of fuel oil and 7,126,000 gallons of aviation gas (approximately twenty-seven shiploads) to ships at sea, in addition to large quantities of ammunition, stores, and replacement aircraft.13

--198--

Map 1. Carrier support during the Iwo Jima campaign

--199--

The Invasion of Okinawa (Operation ICEBERG), March-June 1945

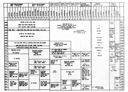

After the invasion of Iwo Jima, the Logistic Support Group returned briefly to Ulithi on 5 March 1945 to prepare for Operation ICEBERG, the invasion of Okinawa. As in the campaign for Iwo Jima, all oilers and other auxiliaries assigned to provide logistic support for the fleet in the battle area were placed under the operational command of Admiral Beary, ComServRon 6. The Logistic Support Group, again designated Task Group 50.8, was directed "to furnish direct logistic support to the Fifth Fleet in and near the combat zone, in order to maintain mobility and striking power."14 Admiral Beary had 125 vessels at his disposal for the invasion of Okinawa, including 39 oilers (see Logistics Replenishment Plan for ICEBERG, fig. 13). Although fleet oilers still constituted its main component, Beary's Logistic Support Group now included a variety of cargo ships, reefers, gasoline tankers, and miscellaneous support ships, as well as the escort carriers and the destroyer screen previously assigned to the Fueling Group. Admiral Beary departed Ulithi onboard the Detroit ahead of the fast carriers on 13 March with 48 ships including 1 light cruiser, 16 oilers, 4 ammunition ships, 4 fleet tugs, 2 airplane transports, 2 escort carriers, 12 destroyers, and 7 destroyer escorts. They steamed to a position of latitude 19°50'N, longitude 137°40'E, where they refueled all four of the fast-carrier groups on March 16. Two days later, four fleet tugs and two destroyers were dispatched to aid the aircraft carrier Franklin (CV-13), which had been severely damaged in a kamikaze attack. The four carrier groups were again refueled on 23 March. For the remainder of the operation, the formation of ships comprising Task Group 50.8 remained within an ocean area located between latitudes 22° and 24°N, longitudes 128° and 132°E. This was about three-days steaming from Ulithi and was close enough to the fleet to supply fuel, food, ammunition, replacement planes, and salvage support as needed.

Fueling and provisioning at sea were now being done on a routine basis using the procedures developed during the previous campaigns. As the operation progressed, fueling schedules were arranged as dictated by the operational requirements of the combat ships involved. Fueling at sea was only undertaken during daylight hours due to the hazards of night maneuvering, especially under the blackout conditions required in a combat area. During the night preceding a fueling rendezvous, the commander of the oiling group would carefully make a check of the wind, weather, and sea state forecast for the rendezvous area in order to determine the best course and speed to set for fueling. The speed and course of the oiler group was set during the night so as to make contact with the fueling group one or two hours prior to the rendezvous time. The oilers then prepared to begin fueling as soon as there was sufficient light.

When the rendezvous was made, three or four oilers would be formed in a single line 1,500 to 2,000 yards apart with a similar line

--200--

Fig. 13. Logistics replenishment plan for

ICEBERG

of ammunition and provision ships 2,000 yards astern of the oilers. While these ships fueled, provisioned, and rearmed ships, oilers not engaged would consolidate cargoes to expedite the return of empty tankers to Ulithi where they would reload from commercial tankers. Fleet-oiler schedules were established prior to sortie from Ulithi with five full oilers originally scheduled to leave every four days. This was later modified to two oilers every three days.

As other Fifth Fleet units approached the objective during the last week in March, the Logistic Support Group ceased to operate solely with the carrier force. Two oilers, the Cowanesque (AO-79) and the Atascosa (AO-66) left Ulithi with minecraft Task Group 52.3 on 19 March. After fueling the group on 22 March, the oilers and two destroyer escorts proceeded to rendezvous with another mine group, Task Group 52.4. After fueling this group, the two oilers reported to commander Task Group 50.8 on 24 March, spent several days with the carrier force, and separated. The Atascosa went to Kerama Retto with the first tanker group to enter the newly acquired anchorage, and the Cowasnesque joined a group to fuel the escort carriers of Task

--201--

By the end of World War II, refueling at sea was being

conducted on a routine basis and had progressed to the point where two

large warships could be serviced at the same time. This maneuver was

not as easy as it may appear as there was always the risk that the

oiler would be crushed by the two larger ships. Here Cahaba (AO-82)--shown 8 July 1945--refuels Shangri-La (CV-38) on her port side and Iowa (BB-61) on her starboard side. Note the

calmness of the seas and the critically small distance between ships.

(National Archives)

By the end of World War II, refueling at sea was being

conducted on a routine basis and had progressed to the point where two

large warships could be serviced at the same time. This maneuver was

not as easy as it may appear as there was always the risk that the

oiler would be crushed by the two larger ships. Here Cahaba (AO-82)--shown 8 July 1945--refuels Shangri-La (CV-38) on her port side and Iowa (BB-61) on her starboard side. Note the

calmness of the seas and the critically small distance between ships.

(National Archives)

Group 50.8 on 1 April. The oilers then went to Ulithi for fresh cargo. This was typical of the procedure followed throughout the operation.

The fuel required for the Okinawa operation far exceeded that consumed during any previous campaign. This large consumption was the result of the many ships employed and an increase in their endurance at sea because of the underway replenishment facilities of Service Squadron 6. Between 17 March and 27 May, the amount of fuel oil, diesel oil, and aviation gasoline issued by Task Group 50.8 for replenishment at sea (including its own use) was 8,745,000 barrels of fuel

--202--

oil (ninety tankers' worth), 259,000 barrels of diesel oil, and 21,477,000 gallons of aviation gasoline. This was more petroleum than Japan managed to import or produce during the entire year of 1944!15

Aviation gasoline and aviation lubrication oil consumed was also materially greater than in any previous operation. Formerly, the standard load of 20 drums of lubricating oil on each fleet oiler adequately met carrier requirements. As the operation extended, each oiler had to carry 75 drums. Continued demand for it, and an average issue of 80 drums daily over a period of one month prompted a directive requiring that fleet oilers leave port with an initial load of 150 drums. Fleet oilers carried numerous other items in addition to their regular cargoes, including gasoline drop tanks, depth charges, arbors, ammunition, dry stores, medical stores, mail, replacement personnel, and passengers, as previously stated. All could be transferred to vessels that were alongside for refueling.

Toward the end of the Okinawa campaign, when the Third Fleet took over the command of the combat fleet, the designation of Service Squadron 6 was changed to Task Group 30.8. It continued to operate in support of fast-carrier groups launching air strikes against the main Japanese islands. One unit of twelve fast oilers and a transport carrier were even sent into the foremost forward operating area under the command of Capt. J. R. Pahl, who was embarked on one of the destroyers assigned to it as escort.16

--203--

Contents

Previous Chapter (17) **

Next Chapter (19)