2

NOTS, the Shipping Board, and the Acquisition of

Merchant Tankers in the First World War

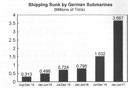

Well before the United States entered World War I, the effects of submarine warfare had begun to have a dramatic impact on the shipping and shipbuilding industry in America. By the spring of 1916 the German U-boat campaign had become so effective that ships were being sunk faster than they could be built. Orders to replace these losses quickly filled the slipways of almost every shipyard in the country. While American yards prospered, they could not meet the insatiable demand for merchant shipping. The shortage of merchant shipping throughout the world forced international freight rates to soar so high that it caused serious disruptions in America's overseas trade. In its endeavors to solve the ensuing shipping crisis, President Woodrow Wilson's administration proposed a government program for building certain types of merchant vessels that it claimed would also be suitable for use as naval auxiliaries. Although the administration talked about the need for naval preparedness, its primary interest was trade. Cargo ships would come first; the main task of the government's fleet would not be to support the navy, but to force reductions in overseas shipping rates.1 The administration's efforts to lobby Congress on behalf of business and trade interests were ultimately successful in gaining passage of the Shipping Act of 1916. As will become evident in the chapters that follow, the events surrounding the establishment of the U.S. Shipping Board and the difficulties it experienced while trying to expedite the construction of urgently needed merchant shipping were to have a profound effect on the navy's future attitude toward merchant shipping and its future plans for war.

An important provision of the new act was the establishment of the United States Shipping Board, an independent agency of the government that was granted sweeping authority to regulate the nation's merchant marine. Composed of five commissioners appointed by the president of the United States and confirmed by the Senate, the shipping board was given extraordinary power over the shipping industry